The Miss Molly I Adventures - Part 4

|

|

Neah Bay to Crescent City

So, after 5 days in the delightful surroundings of Neah Bay, with the weather forecast looking good for the next few days, we headed out past Tatoosh Island to the buoy off Cape Flattery and turned south, destination not-quite-sure-where. The plan was basically to see how it went and to get as far south as we felt comfortable with. For the benefit of those that don't know this part of the world, the north west Pacific coast of the USA is not exactly a welcoming piece of water. It's a desolate, rocky coast, with rocky reefs stretching sometimes as much as 5 miles out to sea. There are very few safe anchorages or ports - in fact, almost none until Crescent City in northern California. Yes, there are the Columbia River, Newport, Coos Bay and the Rogue River, but they all have sand bars in their entrances that have reputations to make the first-time enterer of these harbours think twice about attempting it in anything but the very calmest of conditions.

The Pacific Ocean was, unsurprisingly, quite unlike any water that we'd experienced with Miss Molly I before. Although there was only a light breeze blowing, the ocean swells were 3m (10ft) sine waves with small wind waves on top of that. The movement of the boat was quite different; the sky was overcast and it was distinctly chilly despite it being the middle of June. However, there was enough of a breeze to sail and so we pulled on all of our warm clothes and waterproofs and settled into our watch system on what was sure to be our longest sail to date. We had a vague plan that we'd head initially for Coos Bay, Oregon, but if conditions were looking good and we felt up to it, we'd continue towards Crescent City, California and see how it was going from there. Since Coos Bay was around 350 miles from Neah Bay, we would have to do at least 3 to 4 days and nights non-stop in 3 hour watch shifts.

The movement of the boat in those big ocean swells made both of us feel a little off colour. Neither of us was physically sick, but we didn't eat very much those first couple of days. We did our watches and slept when off duty. On those occasions that we were both awake, we'd chat or sing songs - I remember Van Morrison's "And It Stoned Me" being a particular favourite that we sang over and over again - it had a remarkable spirit-lifting effect.

For ocean navigation, I had completed a celestial navigation course whilst we were in Vancouver, Canada. Though I say so myself, I had done rather well in this and had scored 98% in the final exam, only dropping 2% because I omitted to write the date on the top of the page. We had a plastic sextant on board that I'd picked up for peanuts from Popeye's in Vancouver, along with all of the necessary tables and sheets for position calculation purposes, and I felt competent with it all. What I hadn't foreseen, however, was that we wouldn't see even a glimpse of the sun until our 4th day underway, by which time our dead reckoned position had acquired an element of inaccuracy. But, we stayed close enough to the coast to pick out details through our binoculars, and, soon after dawn of the next day, we sighted Destruction Island.

The wind remained light - dropping somewhat at night and picking up a bit during the day - so we could sail on at speeds varying between 3 and 4 knots. At dawn of the 3rd day, we sighted the Columbia River entrance, with the ocean swells diminishing during that day and night, so that by 10:00 on the fourth day, we sighted Newport, Oregon in conditions that could be described as pleasant. The sun came out, it warmed up a bit allowing us to take off our waterproofs, and we were feeling truly good for the first time on this passage. We decided to head for Crescent City, California.

The Pacific Ocean was, unsurprisingly, quite unlike any water that we'd experienced with Miss Molly I before. Although there was only a light breeze blowing, the ocean swells were 3m (10ft) sine waves with small wind waves on top of that. The movement of the boat was quite different; the sky was overcast and it was distinctly chilly despite it being the middle of June. However, there was enough of a breeze to sail and so we pulled on all of our warm clothes and waterproofs and settled into our watch system on what was sure to be our longest sail to date. We had a vague plan that we'd head initially for Coos Bay, Oregon, but if conditions were looking good and we felt up to it, we'd continue towards Crescent City, California and see how it was going from there. Since Coos Bay was around 350 miles from Neah Bay, we would have to do at least 3 to 4 days and nights non-stop in 3 hour watch shifts.

The movement of the boat in those big ocean swells made both of us feel a little off colour. Neither of us was physically sick, but we didn't eat very much those first couple of days. We did our watches and slept when off duty. On those occasions that we were both awake, we'd chat or sing songs - I remember Van Morrison's "And It Stoned Me" being a particular favourite that we sang over and over again - it had a remarkable spirit-lifting effect.

For ocean navigation, I had completed a celestial navigation course whilst we were in Vancouver, Canada. Though I say so myself, I had done rather well in this and had scored 98% in the final exam, only dropping 2% because I omitted to write the date on the top of the page. We had a plastic sextant on board that I'd picked up for peanuts from Popeye's in Vancouver, along with all of the necessary tables and sheets for position calculation purposes, and I felt competent with it all. What I hadn't foreseen, however, was that we wouldn't see even a glimpse of the sun until our 4th day underway, by which time our dead reckoned position had acquired an element of inaccuracy. But, we stayed close enough to the coast to pick out details through our binoculars, and, soon after dawn of the next day, we sighted Destruction Island.

The wind remained light - dropping somewhat at night and picking up a bit during the day - so we could sail on at speeds varying between 3 and 4 knots. At dawn of the 3rd day, we sighted the Columbia River entrance, with the ocean swells diminishing during that day and night, so that by 10:00 on the fourth day, we sighted Newport, Oregon in conditions that could be described as pleasant. The sun came out, it warmed up a bit allowing us to take off our waterproofs, and we were feeling truly good for the first time on this passage. We decided to head for Crescent City, California.

Day 4 and conditions are improving

Generally speaking, things on board were working nicely. As I've already said, we alternated watches, with the other one either relaxing, or sleeping, or preparing food or tea. The person on watch was pretty much confined to the cockpit. It turned out that my homemade windvane didn't like steering with the wind from abaft, so we had to hand steer, but that wasn't really an issue - Miss Molly I was very light on the tiller and there was almost no effort involved in keeping her on course. All of the sail handling lines were led back to the cockpit, so there was no need to leave the cockpit for anything to do with handling the boat. We wore safety harnesses all the time - there were 3 clip on points in the cockpit area; one beneath the tiller, and one on either side of the aft end of the coachroof. With the double safety line system, we were never unclipped. If there was any need to go forwards, a stout line ran from the clip on points on the aft end of the coachroof to the mast, as a kind of V-shaped life line that one could clip on to. In this way, the boat was safe and easy to handle, so one person could do it all alone without significant risk or exertion.

But the third night at sea had pointed out one problem to us. Our navigation lights had been getting dimmer and dimmer and had finally given up the ghost towards dawn of the third night. Clearly our batteries were not being charged even though we ran the engine for a few hours now and again to top them up. This was probably the same problem that had led us to buy a new battery in Port Angeles. I needed to investigate.

The sea state had certainly calmed, but it was still rolly enough to make working in the engine room a challenge. I checked the obvious things first - belts, wiring connections, etc, and then started tracing the system through with a multi meter. The problem seemed to lie in the voltage regulator, so I opened it up and started tracing it through. It was one of the old-type, mechanical, solenoid type regulators with contact breaker points, and luckily I could just remember something about their function and set up from my days at Brighton Tech back in the late '70s/early '80s. I worked out that a connection had completely burnt away - there was actually no trace of it, but from what I remembered of the function of these things, it surely should have been there. I found a spot where I could bridge two existing connection to make a connection that would replace the one that I thought was missing, cleaned off the lacquer from the copper wires, stripped the ends of a short length of braided copper wire and twisted it tightly in position. I fired up the engine and checked the charging. It worked! We had battery charging again! (Incidentally, I never improved this repair. It worked for all of the rest of the time that we had Miss Molly I!)

The other thing that needed a bit of care was our compass situation. We'd left Vancouver with an antique of a compass that had been part of an old autopilot system. I had liberated it from the rest of the mechanism and mounted it so that its gimballed mounting sat upright just behind the rudderstock. It was, however, unlit, so, in Bainbridge Island, I had fitted a new bulkhead compass with an integral light so we could read it at night. The problem was that neither of these compasses had been properly swung, and both compasses were clearly affected by the mass of steelwork in the hull. I had drawn up a deviation table for each compass that showed deviations of up to 25 degrees on some compass courses - clearly not the sort of deviation that can be ignored. We had to make sure we allowed for this in any aspect of navigation. However, as we were basically heading south, it didn't initially prove to be too much of a problem.

I managed to get a sun sight at noon on the 4th day and calculate our latitude, which, given that we were about 5 - 6 miles offshore, gave us a pretty good position fix. As the day progressed, the wind picked up to a good 20 knots from the north and we made a lively 6 knots with 3 reefs in the sail, sighting Coos Bay by dusk. However, with the night, came fog and no diminishing of wind speed. The ocean waves were building with the continued wind so we decided to head further out to sea to give ourselves adequate sea room. As we were heading southwest, we passed right through a long procession of fishing boats heading out into the seas in a northwesterly direction.

On the morning of the 5th day, the wind had dropped but the fog had got thicker. Now we had a problem in that we were back to dead reckoning of our position and, in the fog, we had no sight of anything to confirm it. We decided to motor rather gingerly in a southeast direction in the hope of stumbling across something that would allow us to get a position fix and, after a while, we did indeed stumble across something - a fishing boat, who we called up on the VHF radio and asked them if they would be so kind as to tell us our position. The position we received put us about 20 miles northwest of Cape Blanco, so we then set a course for the buoy off Cape Blanco and headed on. The fog stubbornly refused to thin and, by the time our DR put us some 6 miles beyond the Cape Blanco buoy, we gave up any hope of seeing it.

The wind picked up again and the seas continued to increase. By this time, it was starting to get a bit uncomfortable out there; we were tired and a bit disturbed by the ongoing lack of visibility and all this fumbling around not really knowing where we were. We briefly considered trying to get in close to Port Orford to see if Cape Blanco offered any protection from the ever-increasing seas - maybe we could even put into Port Orford for some much-needed rest (as far as I can tell, there's not really much of a port there, so I don't think this idea would have worked!) - but the wind continued to increase and the waves continued to increase and we thought better of it.

By now the seas were getting quite significant - big, breaking waves that picked us up on their faces so that we were looking down into their troughs. Cape Blanco is the second westernmost point of the contiguous United States and is surrounded by jagged rocky reefs stretching some miles out to sea and continuing quite a way south down the coast - it is not a place to be near in a seaway, and particularly not if you're not really sure where you are. We headed out again as best we could in the angry seas, steering a course to take the breaking waves on the stern and make some southwesterly progress between the crests. We monitored the weather reports from the NOAA carefully on the VHF radio; the news wasn't good - the forecasts consistently told us that the wind was stronger to the south of us.

The fog thinned a bit, but the sky was dark and foreboding - visibility was still decidedly poor; we were knackered and the prospect of even stronger winds to the south of us wasn't exactly encouraging. Once we'd convinced ourselves that we had sea room again, we decided to drop the sail, lash it securely in a bundle midships and just lie a-hull for a while. Every now and again a breaking wave would roar down and smash against the side of Miss Molly I, knocking her sideways and covering her in water. After only a short while of this, I decided to deploy our drogue (another Popeye's bargain!) in the hope that it would put us more bow to the waves. In "After 50,000 Miles", Hal Roth says that deploying a drogue from the bow slows the downwind drift but typically makes a sailboat lie at close to 90 degrees to the waves. This wasn't quite the case with Miss Molly I. It certainly reduced our downwind drift, but it also turned us to an angle of about 45 degrees to the waves, which was significantly more comfortable - the seas still broke over us and crashed into us with quite some force, and we still rolled around quite a lot, but it somehow felt like it was a bit better - we were doing something about it. We went below and laid down in our 2 sea berths on the midships settees with our lee cloths in position to stop us from being thrown out of the bunks. The sound outside was horrendous, but we got a little sleep.

We were also monitoring the VHF and, at around 18:00, we heard a transmission from the US coastguard. I tried to contact them, but initially had no success, and then, after a while, they heard something from us and answered. We could hear them clearly, but they were receiving only some of my message. More frustration! After some experiments, I worked out that there was a broken wire in the spiral cable that ran from our VHF set to the handset part - if I held it in a certain position it would work. I then made clear contact with the coastguard station at North Bend and informed them of our DR position and situation. I told them we were fine and in no apparent danger, but that we'd like them to know that we were out there. They were excellent - thoroughly professional - and suggested setting up a contact schedule by which we would contact them every two hours and report on our situation.

We continued to get small amounts of sleep in worsening conditions, checking in with the coastguard as arranged. During our 10pm check-in, the coastguard asked if we could see any black objects nearby. I guess they had a radio direction finder that put us on the same bearing as the reef near the Rogue River entrance. I went outside for a look around and was pleasantly suprised to find that the fog had eventually lifted, that there were no signs of reefs being nearby and that we were lying due west of a largish town. The coastguard identified this as Gold Beach, Oregon and, as we estimated our position to be about 6 miles offshore, we were clear of any dangers.

At midnight we were sighted by another vessel, who joined our check-in conversation with the coastguard. The vessel's captain expressed understanding for our situation, saying, "it's not very nice out here" and gave us a position that put us about 4 miles offshore, close to the Rogue River entrance buoy.

We monitored our drift through the night and at 05:00 the next morning, I contacted the Rogue River coastguard station to enquire about the condition of the bar in the river entrance to see if we could consider putting in there. They described the bar conditions as "nice" and said that they would meet us at the bar and guide us in. As the wind and waves had dropped significantly, we made our decision, started the motor, hauled in the drogue, raised sail and began making our way to windward from a position off Cape Sebastian towards the Rogue River entrance.

The wind and waves had dropped, but there was still quite a chop running. This is quite undoubtedly the worst point of sail for a junk-rigged boat - beating into a significant chop in insufficient winds. The wind strength has to be enough to keep the weight of the sail and battens from making the entire sail flap about with the movement of the boat in the chop. It wasn't. We made slow progress northwards. And then the engine lost power. It would still run, but only at a very much reduced r.p.m. Clearly, the bashing about we had received had stirred up some muck in the fuel tank and now the filter was partially blocked. At about 07:00, frustrated and knackered, I called up the Rogue River coastguard again and asked them, since they were coming out anyway, if they'd mind giving us a tow the last bit of the way in. They didn't seem to mind at all, said they'd have to change boats and would be with us in about half an hour. They duly arrived and threw us a tow line which I made fast to our bow cleat and they began to tow us at a highly professional appropriate speed, up into the waves and towards the Rogue River entrance. By 09:30, we were tied up at the commercial dock in Gold Beach, had given our details to the coastguard crew and thanked them, had left a telephone message with the customs people at Coos Bay to clear into Oregon, and were left rather dazed and shocked by the whole experience.

But the third night at sea had pointed out one problem to us. Our navigation lights had been getting dimmer and dimmer and had finally given up the ghost towards dawn of the third night. Clearly our batteries were not being charged even though we ran the engine for a few hours now and again to top them up. This was probably the same problem that had led us to buy a new battery in Port Angeles. I needed to investigate.

The sea state had certainly calmed, but it was still rolly enough to make working in the engine room a challenge. I checked the obvious things first - belts, wiring connections, etc, and then started tracing the system through with a multi meter. The problem seemed to lie in the voltage regulator, so I opened it up and started tracing it through. It was one of the old-type, mechanical, solenoid type regulators with contact breaker points, and luckily I could just remember something about their function and set up from my days at Brighton Tech back in the late '70s/early '80s. I worked out that a connection had completely burnt away - there was actually no trace of it, but from what I remembered of the function of these things, it surely should have been there. I found a spot where I could bridge two existing connection to make a connection that would replace the one that I thought was missing, cleaned off the lacquer from the copper wires, stripped the ends of a short length of braided copper wire and twisted it tightly in position. I fired up the engine and checked the charging. It worked! We had battery charging again! (Incidentally, I never improved this repair. It worked for all of the rest of the time that we had Miss Molly I!)

The other thing that needed a bit of care was our compass situation. We'd left Vancouver with an antique of a compass that had been part of an old autopilot system. I had liberated it from the rest of the mechanism and mounted it so that its gimballed mounting sat upright just behind the rudderstock. It was, however, unlit, so, in Bainbridge Island, I had fitted a new bulkhead compass with an integral light so we could read it at night. The problem was that neither of these compasses had been properly swung, and both compasses were clearly affected by the mass of steelwork in the hull. I had drawn up a deviation table for each compass that showed deviations of up to 25 degrees on some compass courses - clearly not the sort of deviation that can be ignored. We had to make sure we allowed for this in any aspect of navigation. However, as we were basically heading south, it didn't initially prove to be too much of a problem.

I managed to get a sun sight at noon on the 4th day and calculate our latitude, which, given that we were about 5 - 6 miles offshore, gave us a pretty good position fix. As the day progressed, the wind picked up to a good 20 knots from the north and we made a lively 6 knots with 3 reefs in the sail, sighting Coos Bay by dusk. However, with the night, came fog and no diminishing of wind speed. The ocean waves were building with the continued wind so we decided to head further out to sea to give ourselves adequate sea room. As we were heading southwest, we passed right through a long procession of fishing boats heading out into the seas in a northwesterly direction.

On the morning of the 5th day, the wind had dropped but the fog had got thicker. Now we had a problem in that we were back to dead reckoning of our position and, in the fog, we had no sight of anything to confirm it. We decided to motor rather gingerly in a southeast direction in the hope of stumbling across something that would allow us to get a position fix and, after a while, we did indeed stumble across something - a fishing boat, who we called up on the VHF radio and asked them if they would be so kind as to tell us our position. The position we received put us about 20 miles northwest of Cape Blanco, so we then set a course for the buoy off Cape Blanco and headed on. The fog stubbornly refused to thin and, by the time our DR put us some 6 miles beyond the Cape Blanco buoy, we gave up any hope of seeing it.

The wind picked up again and the seas continued to increase. By this time, it was starting to get a bit uncomfortable out there; we were tired and a bit disturbed by the ongoing lack of visibility and all this fumbling around not really knowing where we were. We briefly considered trying to get in close to Port Orford to see if Cape Blanco offered any protection from the ever-increasing seas - maybe we could even put into Port Orford for some much-needed rest (as far as I can tell, there's not really much of a port there, so I don't think this idea would have worked!) - but the wind continued to increase and the waves continued to increase and we thought better of it.

By now the seas were getting quite significant - big, breaking waves that picked us up on their faces so that we were looking down into their troughs. Cape Blanco is the second westernmost point of the contiguous United States and is surrounded by jagged rocky reefs stretching some miles out to sea and continuing quite a way south down the coast - it is not a place to be near in a seaway, and particularly not if you're not really sure where you are. We headed out again as best we could in the angry seas, steering a course to take the breaking waves on the stern and make some southwesterly progress between the crests. We monitored the weather reports from the NOAA carefully on the VHF radio; the news wasn't good - the forecasts consistently told us that the wind was stronger to the south of us.

The fog thinned a bit, but the sky was dark and foreboding - visibility was still decidedly poor; we were knackered and the prospect of even stronger winds to the south of us wasn't exactly encouraging. Once we'd convinced ourselves that we had sea room again, we decided to drop the sail, lash it securely in a bundle midships and just lie a-hull for a while. Every now and again a breaking wave would roar down and smash against the side of Miss Molly I, knocking her sideways and covering her in water. After only a short while of this, I decided to deploy our drogue (another Popeye's bargain!) in the hope that it would put us more bow to the waves. In "After 50,000 Miles", Hal Roth says that deploying a drogue from the bow slows the downwind drift but typically makes a sailboat lie at close to 90 degrees to the waves. This wasn't quite the case with Miss Molly I. It certainly reduced our downwind drift, but it also turned us to an angle of about 45 degrees to the waves, which was significantly more comfortable - the seas still broke over us and crashed into us with quite some force, and we still rolled around quite a lot, but it somehow felt like it was a bit better - we were doing something about it. We went below and laid down in our 2 sea berths on the midships settees with our lee cloths in position to stop us from being thrown out of the bunks. The sound outside was horrendous, but we got a little sleep.

We were also monitoring the VHF and, at around 18:00, we heard a transmission from the US coastguard. I tried to contact them, but initially had no success, and then, after a while, they heard something from us and answered. We could hear them clearly, but they were receiving only some of my message. More frustration! After some experiments, I worked out that there was a broken wire in the spiral cable that ran from our VHF set to the handset part - if I held it in a certain position it would work. I then made clear contact with the coastguard station at North Bend and informed them of our DR position and situation. I told them we were fine and in no apparent danger, but that we'd like them to know that we were out there. They were excellent - thoroughly professional - and suggested setting up a contact schedule by which we would contact them every two hours and report on our situation.

We continued to get small amounts of sleep in worsening conditions, checking in with the coastguard as arranged. During our 10pm check-in, the coastguard asked if we could see any black objects nearby. I guess they had a radio direction finder that put us on the same bearing as the reef near the Rogue River entrance. I went outside for a look around and was pleasantly suprised to find that the fog had eventually lifted, that there were no signs of reefs being nearby and that we were lying due west of a largish town. The coastguard identified this as Gold Beach, Oregon and, as we estimated our position to be about 6 miles offshore, we were clear of any dangers.

At midnight we were sighted by another vessel, who joined our check-in conversation with the coastguard. The vessel's captain expressed understanding for our situation, saying, "it's not very nice out here" and gave us a position that put us about 4 miles offshore, close to the Rogue River entrance buoy.

We monitored our drift through the night and at 05:00 the next morning, I contacted the Rogue River coastguard station to enquire about the condition of the bar in the river entrance to see if we could consider putting in there. They described the bar conditions as "nice" and said that they would meet us at the bar and guide us in. As the wind and waves had dropped significantly, we made our decision, started the motor, hauled in the drogue, raised sail and began making our way to windward from a position off Cape Sebastian towards the Rogue River entrance.

The wind and waves had dropped, but there was still quite a chop running. This is quite undoubtedly the worst point of sail for a junk-rigged boat - beating into a significant chop in insufficient winds. The wind strength has to be enough to keep the weight of the sail and battens from making the entire sail flap about with the movement of the boat in the chop. It wasn't. We made slow progress northwards. And then the engine lost power. It would still run, but only at a very much reduced r.p.m. Clearly, the bashing about we had received had stirred up some muck in the fuel tank and now the filter was partially blocked. At about 07:00, frustrated and knackered, I called up the Rogue River coastguard again and asked them, since they were coming out anyway, if they'd mind giving us a tow the last bit of the way in. They didn't seem to mind at all, said they'd have to change boats and would be with us in about half an hour. They duly arrived and threw us a tow line which I made fast to our bow cleat and they began to tow us at a highly professional appropriate speed, up into the waves and towards the Rogue River entrance. By 09:30, we were tied up at the commercial dock in Gold Beach, had given our details to the coastguard crew and thanked them, had left a telephone message with the customs people at Coos Bay to clear into Oregon, and were left rather dazed and shocked by the whole experience.

We weren't the only boat to have had problems in that vicinity!

Our first job now we were tied up to a dock again, was to dry everything out. It was all either damp or just plain wet - cushions, bedding, our clothes. I guess the fog had infiltrated everywhere; we'd been in and out in our waterproofs bringing wetness in with us, and we'd probably had a few small leaks to add to it all - the deck to hull joint certainly leaked a little in places, maybe the front hatch a bit - none of them were major leaks, but between them and all of the other sources of moisture, things were decidedly less than dry! Luckily, the sky was blue and temperatures were pleasant. In the interior of Oregon, they were going through a heatwave, but on the Pacific coast it was just nice summer weather. We hung everything out over the rails and sail bundle and anywhere else that could be hung upon, and then we went for our first walk ashore.

If you haven't been to sea for a few days non-stop before, you won't know the marvellous feeling of trying to walk on land after coming ashore again. Walking in a straight line is virtually impossible. Everything is moving around. You have to grab on to things at times to stop yourself falling over - sometimes even when you're sitting on a chair. It's an amazing example of the way in which our bodies adapt to make things normal and shows that some of the things that we accept as being so aren't necessarily as we perceive them. Anyhow, we meandered our way up the dock and out of the immediate harbour area, all the way to the harbour coffee shop - a small, friendly-looking place with a longish bar and a few tables along the window. We sat at the bar, ordered coffee and did our best to reacclimatise. This was obviously going to take a while!

As we sat there holding on to the bar to stop it from moving around and doing our best not to look too dishevelled, I discerned an English accent a bit further along the bar (it was a small place, the bearer of the accent wasn't very far away). Somehow we got talking. The accented person was Anita, an Englishwoman who had moved out to Oregon and was working there as an estate agent. I guess our attempts to look not too dishevelled were unsuccessful, because, after a short chat, she said that if we needed a shower, we should come by her place later and use her facilities. So, after a lengthy coffee or two, we headed back to the boat, got our wash stuff and set out on wobbly legs towards Anita's place. We found it and knocked on the door, but there was no one at home. Somewhat disappointed, we turned around and walked back to the boat to spend the rest of the day recuperating.

After a good night's sleep, we were sat back in the coffee shop the next morning when Anita came in. "Did you have a shower? she asked. A little confused, I answered that we'd been by but there had been no one home. "Oh, the door was open. You should have gone in and helped yourselves!".

Anita looked after us for the two weeks that we stayed there in Gold Beach. One thing was for sure, we weren't moving on until we'd improved our navigation equipment. We ordered a handheld GPS via mail order from West Marine and had no intention of going anywhere until it had arrived! During those two weeks, Anita met us several times at the coffee shop, invited us to a barbecue and drove us around to generally see the area, including some of the lovely 5 acre lots that were up for sale on the outskirts of Gold Beach, some of the ocean-front properties she'd recently sold and another delightful ocean-front property that she and her husband owned, had an Airstream trailer on and planned to build on one day.

If you haven't been to sea for a few days non-stop before, you won't know the marvellous feeling of trying to walk on land after coming ashore again. Walking in a straight line is virtually impossible. Everything is moving around. You have to grab on to things at times to stop yourself falling over - sometimes even when you're sitting on a chair. It's an amazing example of the way in which our bodies adapt to make things normal and shows that some of the things that we accept as being so aren't necessarily as we perceive them. Anyhow, we meandered our way up the dock and out of the immediate harbour area, all the way to the harbour coffee shop - a small, friendly-looking place with a longish bar and a few tables along the window. We sat at the bar, ordered coffee and did our best to reacclimatise. This was obviously going to take a while!

As we sat there holding on to the bar to stop it from moving around and doing our best not to look too dishevelled, I discerned an English accent a bit further along the bar (it was a small place, the bearer of the accent wasn't very far away). Somehow we got talking. The accented person was Anita, an Englishwoman who had moved out to Oregon and was working there as an estate agent. I guess our attempts to look not too dishevelled were unsuccessful, because, after a short chat, she said that if we needed a shower, we should come by her place later and use her facilities. So, after a lengthy coffee or two, we headed back to the boat, got our wash stuff and set out on wobbly legs towards Anita's place. We found it and knocked on the door, but there was no one at home. Somewhat disappointed, we turned around and walked back to the boat to spend the rest of the day recuperating.

After a good night's sleep, we were sat back in the coffee shop the next morning when Anita came in. "Did you have a shower? she asked. A little confused, I answered that we'd been by but there had been no one home. "Oh, the door was open. You should have gone in and helped yourselves!".

Anita looked after us for the two weeks that we stayed there in Gold Beach. One thing was for sure, we weren't moving on until we'd improved our navigation equipment. We ordered a handheld GPS via mail order from West Marine and had no intention of going anywhere until it had arrived! During those two weeks, Anita met us several times at the coffee shop, invited us to a barbecue and drove us around to generally see the area, including some of the lovely 5 acre lots that were up for sale on the outskirts of Gold Beach, some of the ocean-front properties she'd recently sold and another delightful ocean-front property that she and her husband owned, had an Airstream trailer on and planned to build on one day.

Rogue River, looking towards the ocean.

And the other way.

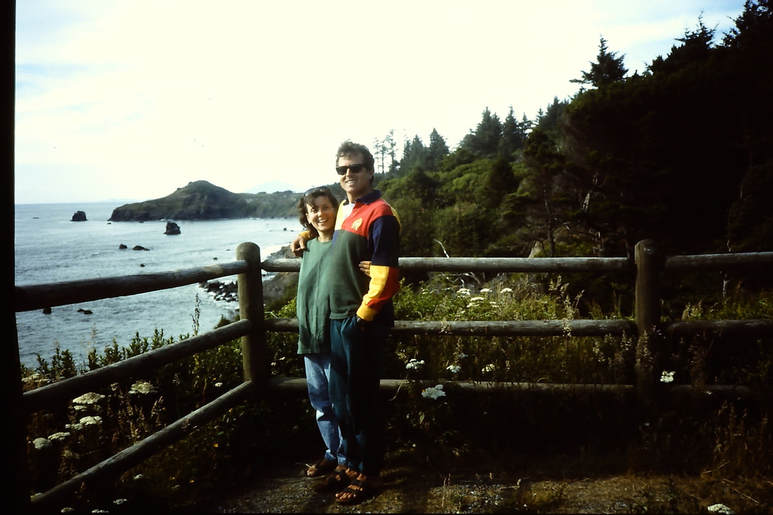

Viewing an ocean-front property

It wasn't all rest and recuperation, although there was rather a lot of it! But we also got ready to head on. It was now the end of June heading into early July. As already mentioned, my brother was getting married in August and we had tickets to fly back to England for that. We would have to get to somewhere where we could safely leave the boat for a while so that we could do that. I cleaned out the diesel system (water trap and 2 filters) and repaired (shortened) the spiral cable on the VHF handset, and when our new handheld GPS arrived, it was time to say our goodbyes and move on.

So, on the 8th July, at 08:10, we left the commercial dock at Gold Beach and headed back out into the Pacific. I cannot deny that, despite the apparent calmness of the day, we had some trepidation. But, we made good time, first motoring in the calm, then motorsailing when a hint of a breeze got up, then sailing in light airs and finally motorsailing again as it began to die down. The new GPS made navigation simplicity itself. In such conditions, I just switched it on every 3 hours, got the lat. long. position and marked it on the paper chart, then switched the GPS off again. Lovely!. I could see no reason for leaving it running all the time. We motored in to the harbour of Crescent City, California at 20:30 after an entirely uneventful trip.

So, on the 8th July, at 08:10, we left the commercial dock at Gold Beach and headed back out into the Pacific. I cannot deny that, despite the apparent calmness of the day, we had some trepidation. But, we made good time, first motoring in the calm, then motorsailing when a hint of a breeze got up, then sailing in light airs and finally motorsailing again as it began to die down. The new GPS made navigation simplicity itself. In such conditions, I just switched it on every 3 hours, got the lat. long. position and marked it on the paper chart, then switched the GPS off again. Lovely!. I could see no reason for leaving it running all the time. We motored in to the harbour of Crescent City, California at 20:30 after an entirely uneventful trip.

Anchored out in Crescent City harbour (that's us in the distance!)

We anchored out in the outer harbour, enjoying the protection of the harbour walls but staying a good distance from the shore and enjoying the peace and quiet out there. We rowed ashore in the dingy and just left it tied to a rock on the beach whenever we went ashore. it seemed perfectly safe there.

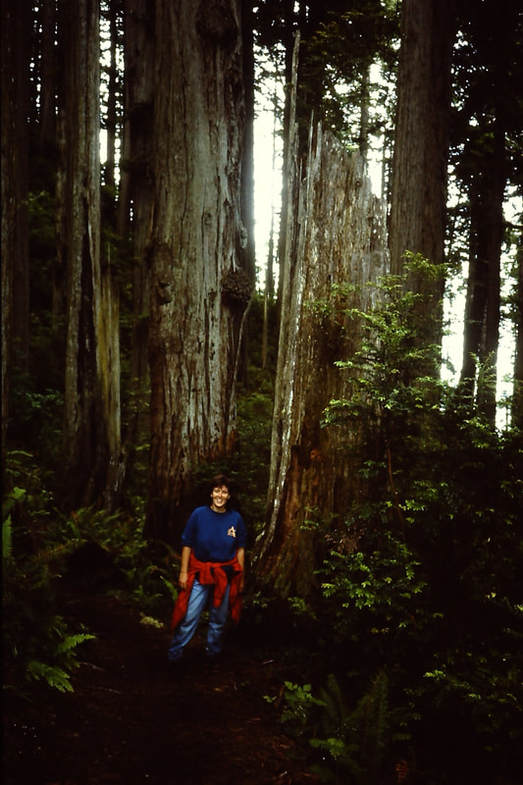

In the photo above, you can see on the upper left that a band of cloud is hanging over the shore there. This is pretty much a permanent feature and leads to the wonderful moist atmosphere that waters the giant redwood forest that grow there. Giant redwoods! We had to go and have a look!

We got up early one morning, rowed ashore and walked the short distance to the bus stop, from where we could catch the morning bus up into the redwood forest. We got out and were instantly amongst the trees. Man, those things are big.... and green... and beautiful :-)

In the photo above, you can see on the upper left that a band of cloud is hanging over the shore there. This is pretty much a permanent feature and leads to the wonderful moist atmosphere that waters the giant redwood forest that grow there. Giant redwoods! We had to go and have a look!

We got up early one morning, rowed ashore and walked the short distance to the bus stop, from where we could catch the morning bus up into the redwood forest. We got out and were instantly amongst the trees. Man, those things are big.... and green... and beautiful :-)

Amongst the giant redwoods

On the old number 1 highway!

The weather was good, the surroundings were good, we were feeling good, we decided to walk the 16 miles or so back to the boat. What a great day!!

On the walk back

From Crescent City southwards, it's posible to 'gunkhole', to make shortish hops down the coast. Our next destination would be Trinidad Head, which, as an anchorage, looked to offer good protection from the prevailing northerlies. We reckoned it would be about a 12 hour trip, so thought we might do it as an overnighter - it was still basically mid-summer and so the dark hours would be very short. On July 14th, at 8pm, with a favourable weather forecast, we headed out of Crescent City. There was no wind to speak of, but as soon as we left the protection of the harbour, we encountered swells coming up from the south. This is not a good sign as waves from the south surely signified a southerly wind to the south of us, and a southerly wind in this part of the world usually means a bit of a blow. We hoisted the sail and sheeted it in hard to damp the motion of the boat and motored on. By 21:15, it was starting to gust from the south. We turned around and headed back to our anchorage in Crescent City harbour.

It continued to blow southerly for the next day and by the morning of the 16th, the weather forecast was warning of strong winds from the south in the next few hours. The forecast seemed to be correct as the wind built during the day, so, in the late afternoon, we upped the hook and motored into Crescent City marina.

And now, I think I'll change my plans, rename this chapter and finish it here. The story will continue in chapter 5; Crescent City to Half Moon Bay. You see, I have the advantage of knowing what comes next!

It continued to blow southerly for the next day and by the morning of the 16th, the weather forecast was warning of strong winds from the south in the next few hours. The forecast seemed to be correct as the wind built during the day, so, in the late afternoon, we upped the hook and motored into Crescent City marina.

And now, I think I'll change my plans, rename this chapter and finish it here. The story will continue in chapter 5; Crescent City to Half Moon Bay. You see, I have the advantage of knowing what comes next!